MALIGNANT

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer. They are most commonly caused by excess sun exposure and in particular sun burns in fairer skinned people. Other factors that can lead to BCC are radiation therapy, immunodeficiency, certain genetic conditions and exposure to arsenic. BCCs are usually locally invasive and only very rarely will they spread to lymph nodes and to distant sites in the body.

Left alone BCCs will continue to grow and invade local structures including nerves, blood vessels and cartilage. They can result in a non healing sore or ulcer that will bleed, become painful and infected. Fortunately most BCCs are identified before this stage and easily treated. Very rarely they can spread or metastasize to lymph nodes and distant sites, this tends to only occur in very large and neglected tumours.

There are three main groups of BCCs:

Superficial

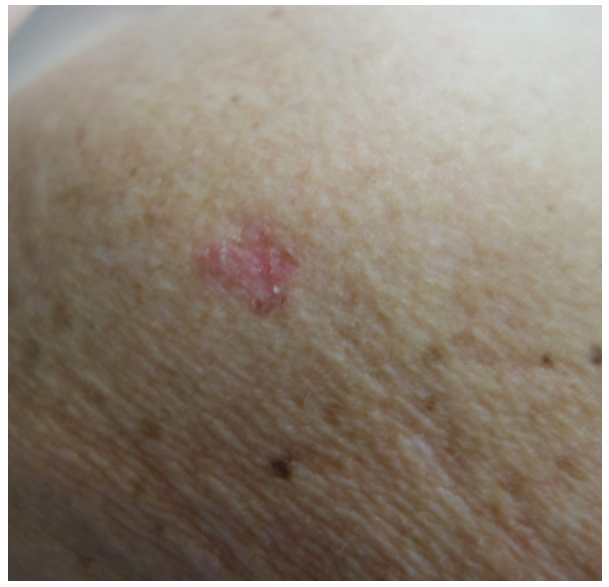

Superficial BCCs as the name suggests grow in the upper layer of the skin. They tend to grow out rather than deep. They appear as a pink patch that will sometimes bleed and ulcerate. They will usually flush to a bright red when rubbed. Left alone they will continue to grow and can become a wound that will not heal. Excision is often the best form of treatment. Some superficial BCCs may be amenable to a cream called imiquimod or Aldara. Other treatments may include cryotherapy, curettage and photodynamic therapy.

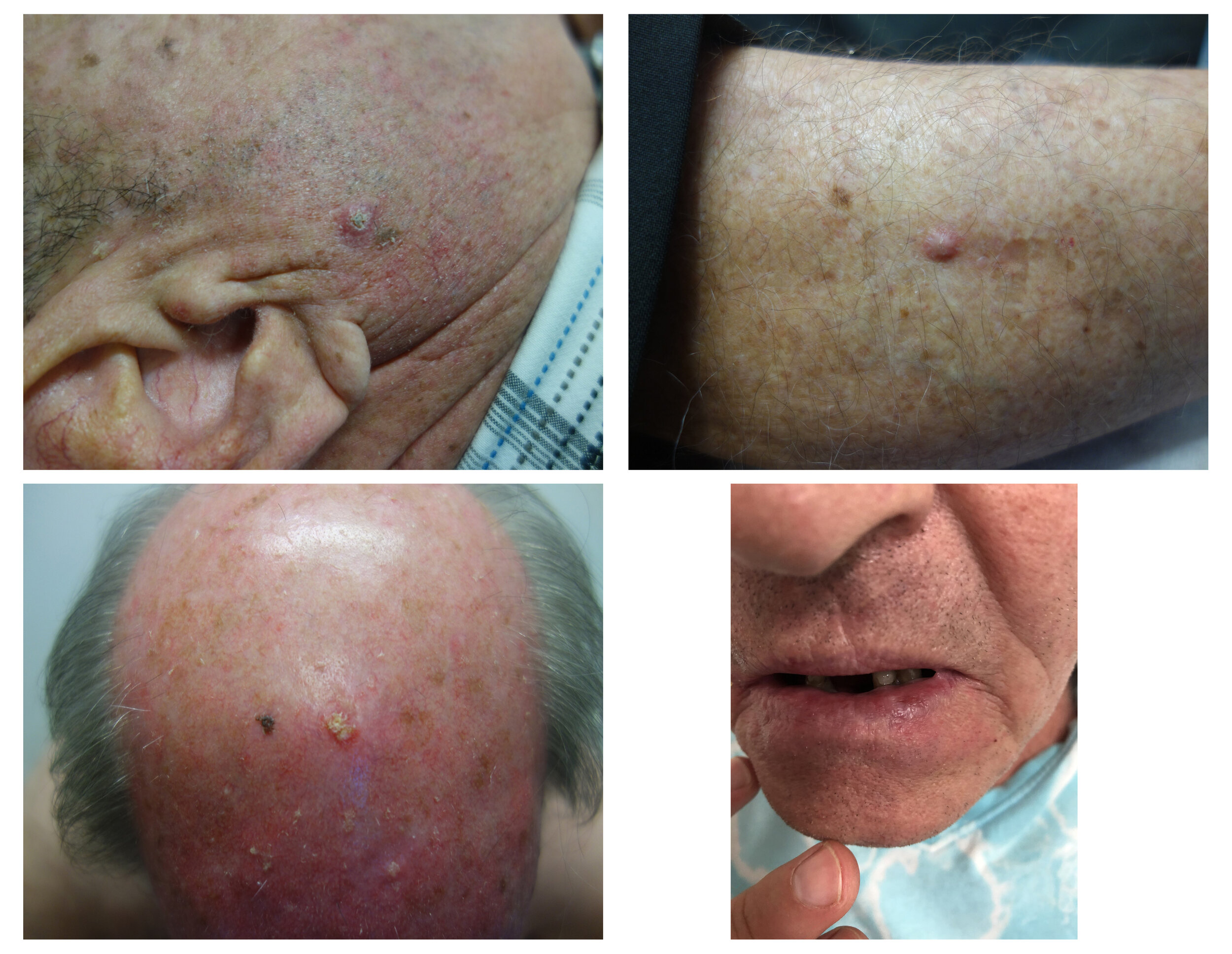

Nodular

As the name suggests, nodular BCC grows in a nodule or dome. They are well defined and easy to determine where the lesion finishes. This makes them easier to treat and a lower risk of recurrence. They grow deeper than the superficial variety so they are unable to be treated with Aldara or cryotherapy. Left untreated they will continue to grow and become locally destructive. They are best excised or on occasions can be curetted. They look like pink, pearly nodules and occasionally will be pigmented with brown and blue. They often have obvious visible branching blood vessels. They may bleed easily.

Aggressive BCCs

The third category is a group of aggressive growth patterned BCCs. They include infiltrating, sclerosing, morpheic and micronodular. These cancers are less likely to grow in a well defined mass and rather spread deeper and wider as a poorly defined lesion. They will have thin extensions that penetrate under the skin and can be difficult to see on the skin surface. They may look ‘scar like’ or present a sore that will not heal or continue to bleed. They are more easily diagnosed by your doctor with dermoscopy and are a good example of why routine screening skin checks are a good idea.

As they can be difficult to visualise and determine the margin, treatment becomes more difficult. They have a higher risk of recurrence after surgery and higher rates of invading nerves. Excision with a wider margin is necessary to ensure clearance. Sometimes in very difficult cases they are best managed by Moh’s surgery. This technique performed by a specialist is a precise surgery completed in stages to ensure complete removal.

Squamous Cell carcinoma

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is a cancer of the skin arising in the squamous cells. Squamous cells lie in the epidermis of the skin and produce an oily substance called keratin. SCC is generally locally invasive and easily treated, however larger lesions and those on high risk sites (face, lips and ears) do have the potential to metastasize or spread which can cause complications and on occasion prove fatal. There are other types of SCC that arise in different organs.

SCC are most commonly caused by UV damage by excessive sun exposure. Risk factors include increasing age, lighter skin, increased sun exposure, smoking, certain genetic disorders, immunodeficiency and transplant recipients. They most commonly occur on sun damaged parts of the body and will sometimes arise out of a preexisting solar keratosis or ‘sun spot’.They appear as a tender, growing, pink nodule and commonly have scale and occasionally a horn.

Most SCCs are adequately treated with a simple excision, On certain parts of the body curettage can be considered. Risk factors for recurrence or metastasis include those larger than 20mm diameter, thicker than 4mm, located on the face, lips and ears and those poorly differentiated. In these cases radiation therapy or further surgery may be considered. 50% of people that are at high risk of SCC will develop another within 5 years. They are also at higher risk for melanoma and other skin cancers.

Intraepidermal Carcinoma/Bowen’s Disease

Intraepidermal Carcinoma (IEC) or Bowen’s Disease is a skin cancer and are a subtype of squamous cell carcinoma. They are superficial cancer occurring in the top layer of the skin called the epidermis. IEC is usually as a result of excessive sun exposure but can be caused by exposure to arsenic. As a result they tend to grow on excessively sun damaged areas of the skin and appear as pink and scaly patches. They can grow horns and may be tender. IEC will increase in size over time but usually spread superficially. They can grow to several centimetres in diameter. 5% will develop into an invasive form of squamous cell carcinoma.

Often excision is the best form of treatment however curette and shaves may also be considered. Non surgical treatments may also be possible including cryotherapy, a cream called fluorouracil (Efudix) cream or photodynamic therapy.

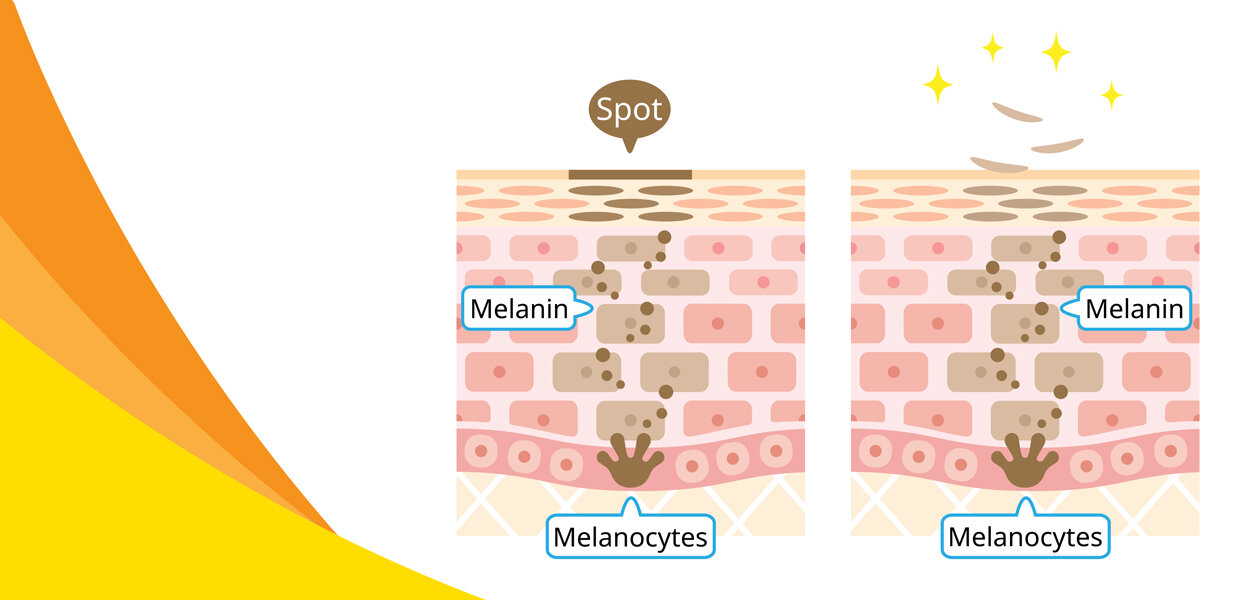

Melanoma

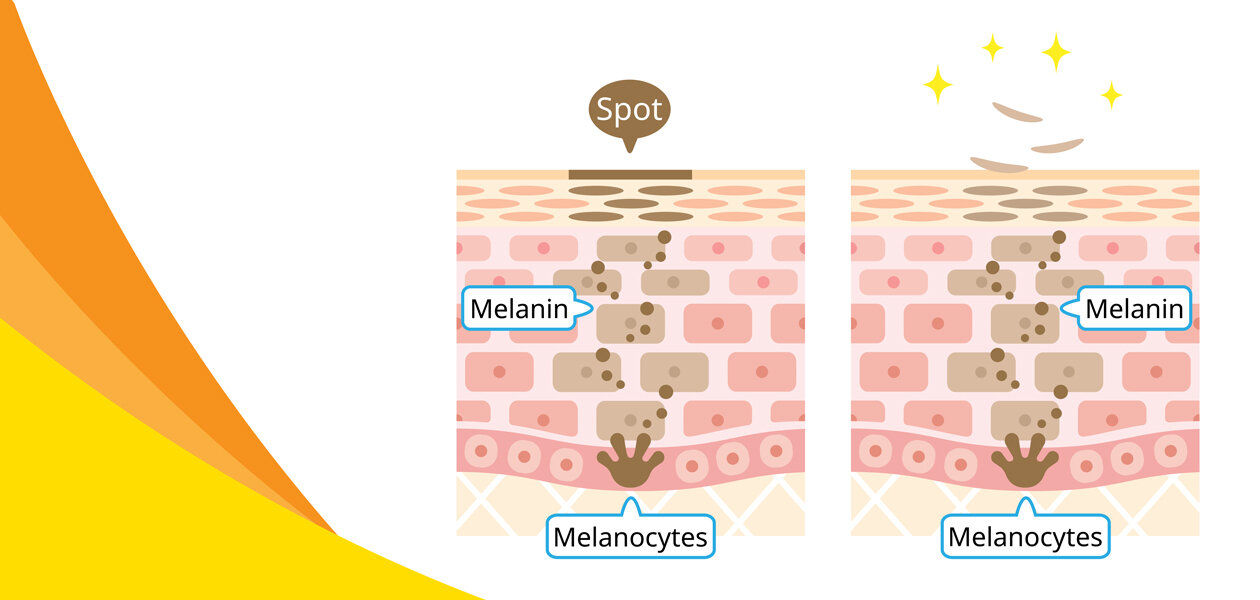

Melanoma is a potentially dangerous cancer resulting from uncontrolled growth of the pigment cells in the skin called melanocytes. Melanocytes produce pigment called melanin and are what gives our skin colour. Everyone has a similar number of melanocytes but how they function and how much pigment is produced will vary. This is what accounts for dark and light skin. Melanin does act as a barrier to our skin cells from UV radiation and this is why darker skinned people are at lower risk for melanoma and other cancers.

Melanomas are complex cancers and there are many subtypes that occur for different reasons. UV radiation through sun exposure is implicated as the cause of many melanomas. The damage can be done through episodic exposure in the form of sun burns or an accumulation of sun damage over a long period of time. Excessive exposure to the sun in the first 18 years of life is thought to especially contribute to your risk of developing a melanoma later in life. Some melanomas occur in clusters in families, there are certain genetic mutations and disorders implicated in the development of some melanomas. Other risk factors include increasing age, male gender, lighter skin, proximity to the equator, increased number of moles and with more variation as well as a prior personal or family history of melanoma or skin cancer.

Melanomas take on many forms, they are generally pigmented brown, black or grey but may be pink. They are usually flat but can be raised. Many grow slowly whilst others will arise quickly in a matter of weeks. Often they appear as a ‘funny looking mole’. They are usually irregular, asymmetrical and don’t look like any other spot on your body. SCAN is an acronym that can help you to identify a melanoma.

S - SORE

Scaly, sore, tender, itchy or hasn’t healed in 6 weeks

C - CHANGING

Changing is size, shape colour or texture

A - ABNORMAL

Looks or feels different or stands out when compared to other moles or spots on your body

N - NEW

Has appeared on your skin recently. Any new moles or spots should be checked, especially if you are over 40.

If your doctor is suspicious a skin lesion may be a melanoma often they will progress to a biopsy. Usually the best course of action is to remove the entire lesion so the pathologist can make a more accurate diagnosis. This can be done in a number of ways including shave, punch or excision and are outlined in the surgical section. Occasionally if they are not sure they may photograph the lesion and ask you to return some time later to review for any change.

If a melanoma is confirmed then it usually requires further treatment. It has been proven that survival rates are increased by taking a wider margin of skin from around the melanoma. The pathologist will provide important information from the biopsy to help your doctor determine how big of an excision is necessary.

A key piece of information is the Breslow thickness, that is how thick the melanoma is. Melanomas have the ability to spread or metastasize to other organs and lymph nodes. This is what makes people unwell and sometimes die. They usually spread by invading blood and lymphatic vessels. The thicker the melanoma the more likely they are to invade a vessel, the higher the risk of the melanoma then the more aggressive the treatment.

In situ melanoma is the very earliest stage and most common form of melanoma. It occurs when the melanoma is contained to the top layer of skin called the epidermis. The epidermis does not contain any blood or lymphatic vessels, so it is impossible for the melanoma to metastasize and so survival rate is close to 100%. Melanomas less than 1mm of thickness are also low risk of invading a vessel. They also have a favourable prognosis with a 98% 10 year survival rate. These melanomas will require a further excision with a margin added.

Melanomas beyond 1mm have an increased risk of metastasis and the risk increases as the thickness grows. Most commonly the first place for the melanoma to spread is the lymphatic node. Your doctor may discuss with you the need for a Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy. This is performed by a surgeon under a general anaesthetic. At the time of the wider excision, dye is injected to the skin where the melanoma arose. This is tracked to the draining lymph node which is removed and then examined by a pathologist to determine if the melanoma has spread.

There have been massive advancements in the way we manage melanoma that has spread to both lymph nodes and distant organs over recent years. With the development of drugs that target the tumour directly or others that target the immune system we have seen survival rates for melanoma improve dramatically.

Many melanomas are entirely preventable by using sun protection. That is avoiding the sun during high UV times, covering up with clothing, hats and sunglasses as well as wearing sunscreen. The key to successful management of melanoma is early detection. It is imperitive to get to know your own skin and be aware of any new or changing lesions. Such spots should be examined by your doctor.

Melanomas can arise anywhere and not all need sun exposure. They can occur on the soles of your feet, finger and toenails and parts that don’t see the sun like your bottom. Some grow slowly and are difficult to detect. Regular full body skin checks by your doctor assists in the early detection of melanoma. They can also occur on the back of the eye called the retina so at least two yearly checks with an optometrist is good practice.

Solar or actinic keratosis are also known as ‘sunspots’ and are very common in our region. Whilst technically not malignant they are considered ‘precancerous’. They usually appear as pink and scaly lesions. They may on occasion sting or itch, especially after sun exposure. They arise on sun damaged areas of the skin, most commonly face, forearms and backs of hands. They are more common in fair skin people and those with extensive sun exposure.

Sun damaged skin is a spectrum of change. Initially it starts out with pigmentation changes and increased freckling. As the UV radiation from the sun causes more damage to the cells, mutation begins to occur. This is when solar keratosis arises.

Early on they will come and go. As the sun causes damage they will flare, become more inflamed, red, scaly and sometimes irritate. If you protect them from the sun your immune system can repair the damage to a degree and you may see the lesions fade. If you get too much sun damage they move past the point of repair, more mutations occur and they progress becoming larger, thicker and more scaly. Eventually they can potentially develop into a skin cancer called a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The risk of a solitary solar keratosis developing into an SCC is relatively low, however a patient may develop many of these over time. For a patient who has more than 10 solar keratoses there is a risk of 10-15% that they will develop an SCC at some point.

Solar keratosis is considered a precancerous lesion. Depending on where it occurs on the spectrum it may require treatment. Early on the recommendation may only be to protect the skin, cover up and wear sunscreen. If the lesion is more advanced but localised it can be easily treated with cryotherapy. If the damage is more widespread than there are a range of creams that may be prescribed to use as a field treatment (these are explored in the management section hyperlink). If your doctor is more suspicious of it having developed into a cancer it may require a biopsy or excision. A lesion that is tender, thicker, enlarging, ulcerated or growing a horn may be suspicious for SCC.

Solar/Actinic Keratosis

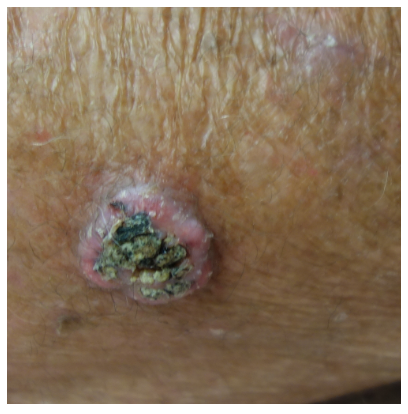

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma (KA) are considered a milder form of squamous cell carcinoma. They usually grow rapidly for a few weeks to form a tender and scaly nodule that ranges from 1 to 5cm. They often resemble a volcano with a keratin core. KA’s will remain indolent for several months and then begin to recede. Several months later they will leave behind the core in the form of a horn.

Keratoacanthoma can on occasion transform into an invasive squamous cell carcinoma. They can also be difficult to differentiate clinically from an SCC. For this reason and because they are usually tender and unsightly excision or curettage is the best form of management.

BENIGN

Seborrhoeic Keratosis

Seborrhoeic keratosis are also known as seb Ks, senile wart or even barnicles. They are a very common harmless warty type spot that arises in adulthood. Some people are particularly prone to them and may have hundreds though almost everyone over the age of 30 will have at least one.

They often have a characteristic appearance but can take many forms

Flat or raised

Smooth or scaly

Often appear waxy and stuck on

Pigmented brown, orange and black or can be nonpigmented

They are no higher risk of developing into a skin cancer and are not a sign of any underlying condition. They increase in number with increasing age and some have a genetic predisposition. They may arise as a result of sunburn, dermatitis or friction as in skin folds. They will often arise from a solar lentigo, a flat pigmented patch.

Often they look suspicious for melanoma to the naked eye but are generally easily diagnosed with a dermatoscope. Occasionally this is difficult and they may need biopsy. Skin cancers can arise through a seborrhoeic and this would necessitate their removal. Otherwise some people find them a nuisance and would like them to be removed. Unfortunately there are no creams that achieve this successfully. Options for removal include cryotherapy, shave removal, laser or excision. However for the vast majority if they do not bother you then the best treatment is to leave them alone.

Solar lentigo are harmless brown often round and flat patches of skin, varying in size from a few millimetres to several centimetres. They arise as a result of UV radiation causing increased production and deposit of the pigment melanin to the skin as an effort to protect the cells underneath. They themselves are not precancerous and do not require treatment. They tend to occur in sun exposed areas and more common in light skinned people. Seborrhoeic keratosis can arise from solar lentigo, in this case a dome or nodule will arise from the flat patch.

Solar lentigo is usually diagnosed easily on examination by your doctor. They can on occasion look very similar to melanoma and may require biopsy. If you do not like the appearance of solar lentigo they can be removed with cryotherapy but this may result in a white mark as a result.

Solar Lentigo

Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibromas are common harmless firm nodules that grow deeper in the skin. They can occur anywhere but more commonly on the arms and legs. They are normally 0.5-1.5cm in diameter and are white, pink and brown. They are firm lumps that are mobile but are tethered to the top of the skin so form a dimple if squeezed.

Dermatofibromas are made of a collection of cells called fibroblasts. They can occur in response to injuries like insect bites or thorns but may arise spontaneously. They are not cancerous and can be left alone though normally will not recede. They are normally easily diagnosed with dermoscopy but can occasionally resemble skin cancers and so may need a biopsy. If they are bothersome to the patient then excision is the best treatment option as they lie deep in the skin.

Moles

The pigment in our skin is supplied by a cell called a melanocyte. Melanocytes are distributed everywhere throughout the skin and everyone has a similar amount. The colour and amount of pigment that they produce is what provides variable skin colour. When these melanocytes grow in a clump or a nest they form a mole or a melanocytic naevus which is technically a benign (non cancerous) tumour. When melanocytes undergo mutations and have uncontrolled growth they become cancerous or a melanoma.

Moles can be congenital and arise early in life or they can be acquired and arise later in life. Sun exposure is thought to be largely responsible for acquired naevi. People with immunodeficiencies will also develop more moles. Congenital naevi arise as a result of genetic factors like familial syndromes and gene mutations. An increased number of moles on one’s body is associated with an increased risk of melanoma. Those with over 100 moles are considered high risk. However it is important to note that an individual mole is at no higher risk of developing melanoma than any other part of the body. So excising a mole won’t prevent a melanoma.

In addition to having large numbers of moles the more variable the morphology (size, shape, patterns) of moles the higher the risk of melanoma. Moles can vary greatly between individuals though usually a person will have 1-2 predominating clones of moles. The more variable the morphology the more difficult it can be to detect the odd one out which may be a melanoma. It is also a reflection of instability of the melanocytes so an increased chance of a mutation causing melanoma.

Dysplastic naevus is a type of mole that looks similar to melanoma, they were once thought to be changing from a mole to melanoma but this is no longer thought to be the case. The dilemma arises in that they can be difficult to differentiate clinically, dermoscopically and also histologically by the pathologist. As a result they sometimes are treated as melanoma to be safe. Growing dysplastic naevi is also a risk factor for developing melanoma.

Moles can arise almost anywhere including the soles of the feet and palms of hands, finger and toe nails, scalp, genitals, retina and conjunctiva of the eye. It has a different appearance at each of these sites. These special site moles are at no higher risk of developing melanoma, though melanoma can occur at these sites also and differentiating them can be difficult. So if there are any concerns it best to seek advice from your doctor.

Normally a mole is easy to distinguish from a melanoma, especially with the use of a dermatoscope. Occasionally moles can look very unusual and begin to resemble a melanoma. Generally if there is any suspicion it is safest to biopsy the mole. Occasionally your doctor may opt to photograph the mole and review it in a few months. If electing to biopsy the mole the pathologist can provide the most accurate report when they see the whole lesion, so normally it is important to remove the mole in its entirety.

If you have a large number of moles that vary in pattern, shape and size it is advisable to see your doctor for regular skin checks as you may be at higher risk for melanoma. Sun protection is also crucial as UV exposure has been implicated in the formation of melanoma.

Sebacous Hyperplasia

Sebaceous glands are associated with hair follicles and secrete an oily substance to lubricate the hair and skin. Sometimes there is an overgrowth of glands and a benign tumour is formed. These are called sebaceous hyperplasia. They look like small yellow and cream lumps and occur mainly on the forehead, cheeks and around the eyes and nose. They are harmless but sometimes can be very difficult to differentiate from a skin cancer called basal cell carcinoma. For this reason they are sometimes excised or biopsied. Otherwise if the patient is concerned individual lesions may be removed by light cautery or if they are extensive a medication called isotretinoin may be considered.

Capillary Angioma

An angioma is benign vascular lesion or overgrowth of blood vessels, there many types. The most common is a Cherry Angioma. It can occur at any age and appears as a red, blue or purple spot or nodule. They are extremely common and some people will have many on their body. Their cause is unknown but they appear to have a genetic component as they can be familial. They are harmless but can look abnormal and appear similar to nodular melanoma, basal cell carcinoma or other skin cancers so require biopsy. They will sometimes bleed and patients will seek treatment. They can be managed with cautery or cryotherapy generally.

Lichenoid Keratosis

Lichenoid keratosis arises when the body’s immune system consumes an existing seborrheic keratosis or solar lentigo, both benign skin lesions. This can occur spontaneously, as a result of trauma, irritation or sun exposure. They generally appear as inflamed scaly flat patches or raised plaques. They can be pink, brown, grey or purple. Their appearance will change over a course of 3-6 months as they begin to disappear.

Lichenoid keratosis are harmless and not at risk of developing into cancers. They can however resemble skin cancers so may require biopsy. If they are particularly bothersome they can be managed with cryotherapy, curette, cautery or shave.

![Intraepidermal[1st]_1645969432.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595402249946-YX2IVVXIFCMX3F6D13Y3/Intraepidermal%5B1st%5D_1645969432.jpg)

![Intraepidermal[2nd]_1347749741.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595402249615-UJTM5QUUQ33VNNVLJ21B/Intraepidermal%5B2nd%5D_1347749741.jpg)

![SolarKeratosis[1st]_1347765149.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595402715527-S46X6YLB1LVY5F3D2QYP/SolarKeratosis%5B1st%5D_1347765149.jpg)

![SolarKeratosis[2nd]_1337685353.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595402714002-2RMR47POJ8DZCQALZABJ/SolarKeratosis%5B2nd%5D_1337685353.jpg)

![SeborrheicKeratosis[1st]_1338849152.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595403192730-SYGDLET77FGQ3GLTJQQW/SeborrheicKeratosis%5B1st%5D_1338849152.jpg)

![SeborrheicKeratosis[2nd]_73743664.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595403193243-EZWAK63SPPM4UH8TAISK/SeborrheicKeratosis%5B2nd%5D_73743664.jpg)

![SeborrheicKeratosis[3rd]_561311746.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595403196318-8ZF237JPY6UFBV50JB9S/SeborrheicKeratosis%5B3rd%5D_561311746.jpg)

![MoleSection[1st]_1458187019.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595403404569-084TQH8O68KW51K1OQ8W/MoleSection%5B1st%5D_1458187019.jpg)

![MoleSection[2nd]_1469292068.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595403404566-Q4AOA2AZMX3SN3ULS1L5/MoleSection%5B2nd%5D_1469292068.jpg)

![Angioma[1st]_661656949.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595403824116-YHDZA2MVOSZILC3NM8G7/Angioma%5B1st%5D_661656949.jpg)

![Angioma[2nd]_784972939.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eeaf63dd2e5876676fd4029/1595403826083-EIP9YGPN20Z7D9DU1095/Angioma%5B2nd%5D_784972939.jpg)